Wearables & Nearables: Sleep is not what it is all perceived to be - by Prof. Michael Gradisar

In this piece sleep expert Prof. Michael Gradisar discusses the history of measuring sleep and its purpose. He addresses the following questions:

Why is measuring sleep important? Why people with insomnia usually misperceive their sleep? What is the influence of wearable sleep tracking devices?

Find an answer to all of these questions in the below article:

With more people buying watches, wearables and nearables that measure their sleep, there is a keen interest in “how much sleep did I get last night?”.

Yet before answering that question, it might be worth asking not only is the wearable or nearable accurately measuring my sleep, but how much sleep did I think I got?

Let’s rewind about 15 years. (p.s. ‘rewind’ is what we did with tape and video cassettes).

The SCIENCE

In 2004, we began measuring a night of sleep of people who came to our sleep clinic complaining of insomnia. And there were two measurements we used.

Polysomnography (otherwise known in the sleep world by its acronym (PSG), or maybe better understood by most as a combination of EEG (measuring brainwaves), EOG (measuring eye movements), and EMG (measuring muscle tone). That’s because brain activity varies greatly during sleep, as do eye movements, and to some extent muscle tone. Although its not perfect, PSG is considered the ‘gold standard’. That means it’s considered the best measurement of sleep, and something to compare all other sleep measurements against.

Once the full night of sleep is recorded, every 30 seconds of data are scored by a trained sleep technician. Their task is to not only state whether each 30-second ‘epoch’ of data is either sleep or wakefulness, but if it is sleep, they also state how light or deep the sleep is. This then produces a polysomnogram, which shows the depth of sleep, and how much.

The second measurement we used was a sleep diary, which meant we were using the person’s perception of what they thought their sleep was like. That meant that in the morning, they wrote down what time they went to bed, how long it took them to fall asleep, how many times they woke up (and for how long), what time they woke up at the end of their sleep, and how much sleep they got. Although this takes more effort to do (compared to syncing one’s wearable), we still think it’s a good measurement of sleep.

As sleep psychologists, we would eventually have both measurements of sleep, and present these to the person dealing with insomnia.

The first thing to note, is that the majority of people with insomnia misperceive their sleep.

Frequency chart of the number of insomnia patients who (mostly) underestimated the amount of sleep they obtained (bars left of zero on the x-axis).

They will more often than not, overestimate how long it took them to fall asleep (ie, say that it took longer to fall asleep than it actually did). Keep in mind that when we fall asleep, we go into light stages of sleep. We roll our eyes side to side in a way that cannot be imitated when we’re awake, and is something that wearables on our wrists cannot measure. Our brain activity shows different types of brainwaves that do not necessarily occur during the day. Yet, we can still have thoughts that go through our minds. And this is likely why people sometimes think that they are awake when they are actually in a light stage of sleep. That’s because their perception is that they were still thinking and thus they must have still been awake.

And for this reason, it also likely explains why people with insomnia underestimate their sleep (ie, say they got less sleep than they actually did). This is because we rollercoaster through light and deep sleep throughout the night. So when we go through some of these lighter stages of sleep, then these times might be perceived as wakefulness instead of sleep.

The ART

From my perception as a sleep psychologist, it was like holding a great deck of cards in a poker game. More often than not, I could see that the PSG was showing the person sitting in front of me was getting more sleep than they thought. That’s because their 'sleep number' on the PSG report was bigger than the person’s estimate. In the early days, I happily laid my cards down … no questions asked.

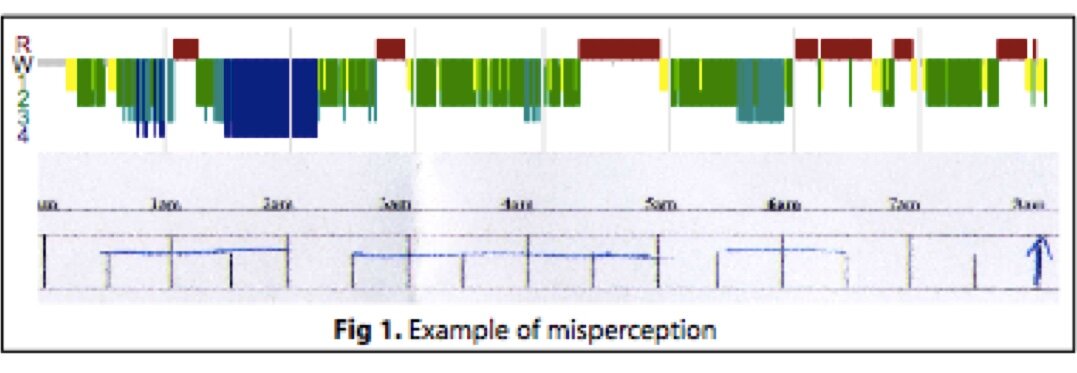

The top coloured graph is a polysomnogram, where the colours show different stages of sleep, and they grey parts (eg, the very start of the night) show when they were awake). The bottom figure is the insomnia patient’s sleep diary for that night (blue horizontal lines indicate when they perceived they were asleep, and gaps indicate when they thought they were awake.

What I didn’t expect was that my good news was not received so well.

“I’ve got a bone to pick with you”

“So you’re saying I don’t have a problem?”

“Great. I thought this was going to explain the fatigue I’ve been experiencing….”

These were just some of the comments fired back at me. It took me a few months in the early days to realise there’s an art in delivering the science.

Listen to My Muscle Memory

When people complete a sleep diary, they make ‘time estimates’.

They’ll think about the last time they saw the clock. And then they will recall what they did, or the range of things they thought about when lying still in the dark. Then they’ll sum it all up and write down when they were asleep or awake. In this way, they are reflecting on what their last memories of being awake were.

And this is where memory - or a lack of memory - is important when perceiving sleep.

Here's why.

In 2004, we performed a trial where we provided feedback about their own PSG-recorded sleep to 1 group of patients with insomnia, and another group did not receive feedback. We called this feedback ‘Sleep Perception Training; Gradisar et al., 2007). Both groups received cognitive-behaviour therapy for insomnia (CBT-I). and at the end of treatment. Yet, both groups improved their sleep at the same rate. Importantly, they received the feedback on their sleep a couple of weeks after their sleep was recorded.

From Gradisar et al., 2007, Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, page 723.

In another study, insomnia patients were given feedback about their sleep recorded with a wearable, the following day after it was recorded. The insomnia patients were found to more accurately predict how long it took them to fall asleep.

Finally, in his penultimate PhD experiment, Jeremy Mercer provided immediate feedback to insomnia patients at various times throughout the night. When these patients were followed up, their sleep had improved.

These studies suggest in order to change someone’s perception about their sleep, the memory of that sleep needs to be very recent. In the end, if someone is experiencing ‘sleep misperception’, it comes down to which one they trust the most - their perception of their sleep vs. a wearable or nearable. How much they trust the device to accurately measure their sleep, will ultimately influence the chances of them shifting their perceptions.

But it’s not only people with insomnia that have shown sleep misperception. At WINK, we’re one of the world leaders in the treatment of body clock issues - for example, Delayed Sleep Phase Disorder (DSPD), which is very common in teenagers (if you’re a parent or a health professional that knows of this problem, you’ll want to see this). We found that only females with DSPD misperceived what time they fell asleep. That is, on average, they thought they fell asleep 45 minutes later than when their wearable thought they fell asleep (the difference for males was only 4 minutes). This is a classic example that shows sometimes it’s about the accuracy of the wearable, and other times, sleep misperception plays a bigger role!

Written by Prof. Michael Gradisar

Leave a comment